Architecture in the City representing the Federal Government

The federal presence was manifested in the capital city of Virginia just before the start of the Civil War by an impressive, permanent granite building. After years of using rented or borrowed accommodation for federal officials, the U.S. Government eventually provided antebellum Richmond with yet another special building type new to the city and a further clarification of the city's urban scale. It was located on a key site in the civic plan that helped, by its relative position, to clarify the constitutional relationships of state, local, and Federal elements in the overall polity. By means of its kinship in form and material with similar buildings built by the federal government across the nation, it clarified its unique position in the Virginia capital.

The Tariff Act of 1790 set up a system whereby tariffs were collected on imported goods at all ports of entry. Tariffs provided the largest source of federal revenue until the introduction of the income tax in 1913. The American government began building architecturally distinguished custom houses in the early nineteenth century. They were primarily intended to house the officials who regulated the export and import of goods and collected customs fees on imports. The officials had formerly been accommodated in warehouses where the goods were kept.

These were modeled on British customs houses and commissioned for major centers of shipping. Places in which to collect customs at ports of entry had existed since medieval times. One of the earliest purpose-built custom houses standing in England is the Exeter Custom House, designed by Richard Allen and built between 1680 and 1681 and. With its originally open, arcaded first floor, the five-bay brick building resembles a town/ market hall. It has an elaborately plastered “long room” on the upper floor and an earth-floored “strong room” on the lower level. Wren’s post-fire Custom House in London of 1671 and its successors of 1717-25 and 1813-17 were architecturally impressive landmarks on the Thames, each containing a “long room” on the main floor where duties were paid [[http://www.hm-waterguard.org.uk/Offices%20&%20Buildings-England.htm].

The expanding federal court system needed space in the city as well. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, each state had a district court in which a judge heard cases involving admiralty and maritime law and minor federal crimes. More important federal cases were heard circuit courts, which met in the same districts, served by two (later one) Supreme Court justices and the district judge. This system continued largely unchanged until after the Civil War.

In Richmond, federal officials were indifferently housed for many years. Customs officials had for many years been located in a warehouse on Fifteenth Street. The post office had been located in a series of buildings, including the former museum building on Capitol Square and the Exchange Hotel. By the 1840s, Richmond's customs officials were housed in a three-story brick building on Fourteenth Street between Man and Cary, near the City Dock [Virginia Mutual Policy 12610, 1844].

The Tariff Act of 1790 set up a system whereby tariffs were collected on imported goods at all ports of entry. Tariffs provided the largest source of federal revenue until the introduction of the income tax in 1913. The American government began building architecturally distinguished custom houses in the early nineteenth century. They were primarily intended to house the officials who regulated the export and import of goods and collected customs fees on imports. The officials had formerly been accommodated in warehouses where the goods were kept.

|

Exeter Custom House [[http://www.hm-waterguard.org.uk/Offices%20&%20Buildings-England.htm]

|

|

Christopher Wren’s London Custom House of 1671 [http://www.hm-waterguard.org.uk/Offices%20&%20Buildings-England.htm]

|

|

The busy Long Room in the London Custom House, where ships were reported

and duties were paid on goods c. 1750.

|

In Richmond, federal officials were indifferently housed for many years. Customs officials had for many years been located in a warehouse on Fifteenth Street. The post office had been located in a series of buildings, including the former museum building on Capitol Square and the Exchange Hotel. By the 1840s, Richmond's customs officials were housed in a three-story brick building on Fourteenth Street between Man and Cary, near the City Dock [Virginia Mutual Policy 12610, 1844].

Interestingly, like their British predecessors, American custom houses drew on the long-established tradition of market halls and courthouses. And, unlike the earlier brick and stucco-clad masonry civic buildings of most local and state governments, the new federal buildings were the first in their neighborhoods to be clad in expensive and permanent cut stone. Like other civic buildings in the period, the more important mid-nineteenth-century custom houses employed fully developed classical forms, but in smaller cities the use of the orders was restricted to the entablature. These "market hall" inspired buildings frequently employed arcades as a principal exterior feature and utilized an fashionable Italian idiom for cornices and architectural details.

In the antebellum period, the central government commissioned a series of significant new custom houses in major cities, designed not only to provide a dignified setting for the functions of the national government and to enable the effective regulation of international commerce, but to house other federal functions, such as courts.

Bank Street façade of the Richmond Custom House, 1865 [LOC]

The Richmond Custom House

Supervising Architect of the Treasury Ammi Burnham Young produced the design for the Richmond Custom House in 1858, as he did for all the federal buildings built between 1849 and 1860. Most were intended to be fireproof and were built of granite. The floors were supported on brick segmental arches spanning between cast iron interior structural members, using recently developed building technology widespread by 1850 [Sara E. Wermiel. The Fireproof Building, 2000]. In most cases the first floor contained a post office, the second floor held the customs office, and the third floor housed a federal courtroom. Young chose a modern, astylar Italianate manner for the form and detail of the custom house.

Supervising Architect of the Treasury Ammi Burnham Young produced the design for the Richmond Custom House in 1858, as he did for all the federal buildings built between 1849 and 1860. Most were intended to be fireproof and were built of granite. The floors were supported on brick segmental arches spanning between cast iron interior structural members, using recently developed building technology widespread by 1850 [Sara E. Wermiel. The Fireproof Building, 2000]. In most cases the first floor contained a post office, the second floor held the customs office, and the third floor housed a federal courtroom. Young chose a modern, astylar Italianate manner for the form and detail of the custom house.

As mentioned above, custom houses had, since the eighteenth century, been modeled on market halls, often with lower-story arcades and upper-story offices. As the building type increased in significance as a local representation of the national government, custom houses in the largest cites also took the form of palaces or temples, sometimes including a central dome and a colonnade or pedimented portico. Among Young’s designs, however, the level of architectural expression was scaled to the size and importance of the host city. All the Virginia custom houses, even the most elaborate, retained the architectural imprint of the market hall. In each design, the separation of functions was maintained by the provision of distinct entrances to each from the exterior.

|

| The Custom House in Norfolk, Virginia. Architect, Ammi B. Young, 1858 [LOC]. |

Norfolk, as a major port, had received its first formally designed custom house in 1819. Norfolk’s new custom house of 1858 took the form of a Corinthian temple, but, like a classical market hall, stood on a raised basement with regularly spaced entries. The Richmond Custom House, at a smaller scale appropriate to the city's status as a port, retained the market-derived arcades in the forms of an arched loggia fronting on Main Street and an arcaded porch on Bank Street.

Similarly, Petersburg’s Italianate Custom House, completed in 1858, had an arcaded ground floor. Two doors in the arches on the north front gave access to a post office vestibule, while the third opened onto the stair to the custom house office. There was no courtroom in the Petersburg building, but a third story containing sleeping apartments for the officials was added to the iron-framed, granite-clad building during construction [HABS documentation]. A small public piazza in front of the Custom House was enclosed by an ornamental cast iron fence and paved with "North River flagging" and flanked by "grass plots, ornamented with trees" [Petersburg Daily Express, 22 Dec. 1858, 1, quoted by HABS].

The Alexandria Custom House of 1858, containing also the post office, and U.S. district court, was even smaller, but featured attached pilasters and a full entablature. Each of the Virginia custom houses was conceived as a free-standing civic building at the urban scale and was placed on an expansive public lot with room for expansion. Richmond’s custom house was set apart from the commercial buildings along Main Street by a pair of flanking courtyards shielded by cast-iron fences and gates. The post office was on the first floor, the customs offices on the second floor, while the third floor held the federal courtroom.

|

| The Custom House in Petersburg, Virginia. Architect, Ammi B. Young, 1856-58 [LOC]. |

|

| The Custom House in Alexandria, Virginia. Architect, Ammi B. Young, built 1858, enlarged c 1903, and demolished c 1930 [LOC]. |

|

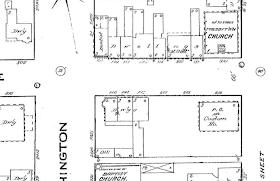

The Alexandria Custom House located close to the street on its public square at the corner of Prince and St. Asaph streets on 1885 Sanborn Map

|

|

Beers' Map of 1877. Detail Showing Capitol Square with the Custom House directly south of the Capitol. The site of the City Hall of 1816 is shown north of the Capitol as a public square.

|

The Richmond Custom House’s position as a special building at the urban scale was as carefully composed as were those of Richmond’s other civic

buildings. The City Hall of 1816 stood almost directly behind and facing the

north façade of the Capitol, making a powerful alliance between the life of the

city as state capital and as metropolis. The federal relationship was even more

effectively expressed by placing the custom house fully on axis with the

Capitol’s south front, along the bottom edge of Capitol Square (see the 1858 drawing below). City Hall was

located on busy Broad Street, the city’s principal thoroughfare, and the custom house was allied with, but separated from, the city’s banks and stores in Main

Street’s commercial center. The custom house and post office facade was aligned with the commercial streetfront, while the courthouse front was set back as befitted as civic building.

While the post office was directly accessible to its many clients along Main Street, the entrance to the federal court faced the Virginia legislature from the foot of Capitol Square. The Richmond Custom House was effectively terraced into the hillside at the foot of Capitol Square, so that it appeared to be only two stories in height on its northern front. A balustraded retaining wall across the north edge of the lot permitted below-grade windows in all the first-floor rooms.

While the post office was directly accessible to its many clients along Main Street, the entrance to the federal court faced the Virginia legislature from the foot of Capitol Square. The Richmond Custom House was effectively terraced into the hillside at the foot of Capitol Square, so that it appeared to be only two stories in height on its northern front. A balustraded retaining wall across the north edge of the lot permitted below-grade windows in all the first-floor rooms.

Main Street façade of the Richmond Custom House of 1858

[Beers Atlas 1876].

Enlargement and Expansion

As a result of its multi-purpose function, internal subdivision, and substantial form, the Richmond Custom House was chosen to serve as the principal government office building for the newly founded Confederate government. The building not only housed Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ office, but the third-floor courtroom was the site of his trial after the end of the war.

The Custom House was enlarged in 1887-89 by the addition of wings at each corner. The inclusion of a new pediment at the center of the Main Street front set the structure even more apart as a public building. The Bank Street façade appears to have been moved north, closer to the street, to increase the size of the building. Its importance increased with the establishment of the federal intermediate court of appeals system in 1891. It housed the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth District.

The Custom House was enlarged in 1887-89 by the addition of wings at each corner. The inclusion of a new pediment at the center of the Main Street front set the structure even more apart as a public building. The Bank Street façade appears to have been moved north, closer to the street, to increase the size of the building. Its importance increased with the establishment of the federal intermediate court of appeals system in 1891. It housed the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth District.

Richmond Custom House, c 1900, after addition of side wings in 1887-89 [http://www.fjc.gov/history/courthouses.nsf/getcourthouse?OpenAgent&chid=AFD1D82C40B6D0F48525718C004B08AD].

North front, Richmond Custom House, c. 1900

[Wikipedia].

South front, Richmond Custom House, c. 1900 [postcard,

Wikipedia].

In the past, the only limit to the footprint of a building was the block on which it stood. Since the custom house was placed at the center of its half-block site, it was able to gradually expand to fill all the space available without losing its imposing symmetry. The reach of the Federal judiciary expanded greatly in the early twentieth century. Additions in 1912 and 1932, including the addition of a fourth story under a tiled, hipped roof, transformed the structure into a massive, symmetrical, five-part palazzo. This included a careful reworking of the rhythm of the Main Street façade by the addition of advanced entries flanking the central loggia. Recessed light courts along the north front give the Bank Street façade a very different character.

Richmond Custom House (by this time known as the

Post Office) after the addition to the west

of 1912 [Wikipedia].

Post Office) after the addition to the west

of 1912 [Wikipedia].

Expanding Traditional Buildings

Because architects in the early twentieth century were not constrained by any qualms about continuing the design features employed during an earlier era, the building could be expanded without a loss of architectural consistency. Adaptation of the Italianate forms first employed by Ammi B. Young allowed later architects to maintain an effective architectural setting that successfully contributed to the streetscape even as it met the changing needs of both the federal court system and the US Post Office.

The fully developed Richmond Federal Court House/Post Office in 1958

showing the addition to the west of 1912 and the addition to the east of 1932

[http://www.fjc.gov/history/courthouses.nsf/getcourthouse?OpenAgent&chid=AFD1D82C40B6D0F48525718C004B08AD]

The south front today [http://www.gsa.gov/portal/ext/html/site/hb/category/25431/

actionParameter/exploreByBuilding/buildingId/680].

.

When the building’s functions grew too large for the block, a typical local solution was employed in 1935-- a bridge to a new building on an adjacent block. Finally, the post office component was moved to a suburban location, freeing up the building for exclusive use as the Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Federal Courthouse, today the oldest such building in continuous use in the nation. The diagram below indicates three phases of the building's growth over time.

Drawing by Thomas Franklin of custom house evolution.

Wikipedia [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:

Lewis_F._Powell,_Jr.,_United_States_Courthouse,_1858-1935_Drawing.TIF]