The ‘old Theatre near the Capital’…was so far old, that the walls were

well browned by time, and the shutters to the windows of a pleasant neutral

tint between rust and dust colored…

Within, the play-house presented a somewhat more attractive appearance.

There was ‘box,’ ‘pit,’ and

‘gallery,’ as in our

day; and the relative prices were arranged in much the same manner.

—

John Esten Cooke, 1854

|

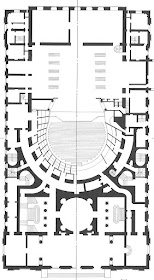

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, 1813 |

|

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London, |

The ancient building type known as the theater is, in the most general sense, where the community gathers to remember the great deeds of the past and to imagine the future. From the Renaissance to the early twentieth century theatres incorporated tightly curving plans and raked stages derived from what was known of the ancient theaters of the Greeks and Romans. This tight arrangement allowed each theater-goer present not only to enjoy the spectacle of an opera or play, but to participate in the collective experience of a gathered company. The Renaissance interpreted the form and content of classical drama in ways that continue to affect theater design today, basing their work on surviving texts and the accessible physical fabric of actual theaters.

The theaters of the continental Renaissance had virtually no exterior presence, since they served the court and were located within the princely palace. As drama became democratized in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, the theater emerged from the palace to take its place as a civic building, equipped for this role with the elements of the classical orders.

On the interior, the intention was not to produce a realistic illusion, but instead, through sumptuous music and art to transform and inform the vision of an entire community. American theaters by the mid-nineteenth-century were well equipped, spacious, and architecturally sophisticated. Never simply a place of amusement, theater managers followed a conventional program incorporating in the same evening popular entertainment and dramatic works that stimulated the moral imagination. In order to take its place in the civic order, the theater was given a prominent location and a high level of architectural finish, often including a fully articulated architectural order.

Background

Most American theaters in the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries, like their European models, were urban buildings in which the

height of the stage and auditorium were concealed behind a classical streetfront.

While stages tended to be very deep, they did not have tall fly lofts. Lobbies

were often minimal in size

and scale. Demands associated

with the development of the dramatic art and the expansion of building

amenities caused a gradual bloating of the structure housing the theater, which

continues to this day. The nineteenth-century impulse to present theaters and other

buildings as singular temple-form structures became problematic as the

secondary features of the theater form, such as the fly loft and lobby,

expanded.

The interiors of many of the nation’s most sophisticated

nineteenth-century theatres were inspired by London’s

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. This famous building, as rebuilt in 1812, utilized

the baroque horseshoe theater or opera house plan, with several tiers of boxes

and sloping seats arranged in a horseshoe shape around a central floor or pit. |

|

St. Charles Theater, New

Orleans of 1843 shows the familiar form derived from the Theatre Royal, Drury lane.

|

|

| Study Model of The Old Theater, Williamsburg, from http://research.history.org/vw1776/revcity/ |

Archeology at the site of the 1752 theater shows it to have been an earthfast frame structure measuring about 72 feet in length and 44 feet in width and built of posts spaced about eight feet apart. Traces of a brick foundation at the west end indicated some sort of brick entrance. A large excavation at the center, bounded by a low brick wall near the center of the building, would have been the “pit” which held much of the theater’s audience. The stage took up approximately half of the theater’s volume,

These itinerant companies developed a touring circuit and, whenever possible, presented their plays in actual theater buildings, sometimes even constructing their own prior to their first scheduled performances in a city. Typical Colonial theaters were relatively large structures, measuring at least 70′x30′, and resembled provincial theaters found in England at the time. The interior of the theater would have exhibited a large stage area on one end, possibly taking up as much as half of the building. An unusual characteristic of eighteenth-century stages was that they were commonly lined with a set of iron spikes designed to discourage audience members from getting onto the stage to disrupt the performance. The seating within the theater was divided into three sections. In front of the stage, sunk below the ground would have been the pit, crammed with benches. The most expensive seating was in the boxes around the sides and back of the theater. The cheapest seating was in the gallery located around the theater above the boxes. . . .An evening at the theater in the eighteenth century would have consisted of two plays, a longer opening play and a shorter and lighter concluding one, and possibly several entr’actes.Virginians were never long without access to theatrical performances. A single thread of theatrical endeavor was nearly continuous with the colony’s urban history, beginning in 1718 and corresponding closely to the annual gathering of leaders associated with the legislative function. Theater was, however, temporarily discouraged by the authorities as frivolous during the Revolutionary War.

Theater in Early and Antebellum Richmond

The capital was moved to Richmond in 1779. Clearly, one of the essential urban building types that moved with the capital to Richmond was the theater, direct heir of its predecessors in Williamsburg. Indeed, the second act of the “Common Council” of the newly formed City of Richmond at its meeting on July 3, 1782 was to require that Mr. Ryan, the theatre manager, account for the number of performances “since the last settlement” and pay the required tax. The first theater building for which there is a record stood on Main Street near the market. This “old theater” was mentioned in 1788 [Christian, 1912].

A large frame school building was built in 1785 on the “Academy Square,” in “Turpin’s Addition” on the eastern slope of Shockoe Hill. It faced west, fronting on Twelfth Street. After the academy failed to prosper, the building, known as the “New Theatre,” was leased to Hallam and Henry, a successor to the English company that had previously put on plays in Williamsburg. According to early historian Samuel Mordecai, Hallam and Henry converted the Academy into a theater, "and here the tragic and the comic muses first bestowed their tears and smiles — in an edifice devoted to them — on a Richmond audience." The Beggars’ Opera was performed in 1787. This building served for theatrical purposes until it burned in 1798.

|

The new Richmond Theater of 1808 at the back of the Academy lot, shown at the letter "P" on the Young Map of 1809. |

|

| Latrobe's extraordinary drawing of the disorderly state of the Green Room at the Richmond Theatre in 1798 |

|

Section through Latrobe's Theater |

After 1802, plays were performed in the hall over the market

house and in “Quarrier’s Coach-shop”

at Cary and Seventh streets until a new brick theater was built in the

rear of the “Academy or Theater Square”

in 1806. It was this three-story building that burned, with terrible

loss of life, in 1811 and was memorialized by the construction of Monumental

Church on the site.

Management and funding for the theater were always a problem, but in spite of that Richmond saw about three hundred different plays, some repeatedly, in the years between 1819 and 1838, including fourteen of Shakespeare's. Twelve of these were written in Richmond [Agnes Bondurant, Poe's Richmond, 1942]. During this period Richmond was a major theatrical center, typical in its tastes and requirements to other cities up and down the eastern seaboard.

The Marshall Theatre, of which no image survives, burned in

1862, likely as a result of arson. Losses included “the valuable

scenery, painted by the elder Grain, Getz, Heilge, and Italian artists employed

by George Jones; all the wardrobe and "property," including some

costly furniture and decorations; rich oil paintings and steel portraits of

celebrated dramatists; manuscript plays, operas, and oratorios, all are

involved in the common destruction. . . in addition to the whole stock

wardrobe. . . [while] the orchestra lost between $300 and $400 in instruments

and sheet music” [Richmond Daily Dispatch, 6 Jan

1862]. The company and theater were managed by Gilbert. Junius Brutus Booth

appeared there in 1821 in his first appearance on the America stage. The

Marshall saw appearances by many of the great actors of the day, including

Edwin Forrest, Charlotte Cushman, John Drew, and Joseph Jefferson, as well as

Edwin and John Wilkes Booth.

Although no image of either the interior or the exterior

survives, it seems likely, based on examples in other cities, that the

auditorium included, in addition to the central pit filled with benches, a

proscenium flanked by classical columns, perhaps similar to the 1798 Park

Theater in New York, seen below.

|

|

The Park Theatre in New York, built in 1798, occupied a stone

structure.

|

|

|

Richmond

Times-Dispatch, 9 Oct 1938

|

While there was enough business for only one theater for the city's first century-- from about 1782 until 1886, it was not the only assembly hall. At first, public events were held mostly in the Masons' Hall of 1787 or the Market Hall of 1794. As the nineteenth century progressed, other venues for shows, concerts, lectures, and meetings were built across the city, often on upper floors to serve a primary purpose as meeting rooms for various organizations. Corinthian Hall on Main Street was the site of Adelina Patti’s concert in 1860. Odd Fellows Hall was used for public events from 1842 to 1858. Metropolitan Hall was opened in 1853 with the adaptation of the former First Presbyterian Church building of 1828 for secular audiences. It stood on the northeast corner of Fourteenth and Franklin streets. According to Mary Wingfield Scott, it was used for “lectures, theatrical entertainments and political conventions, and later as a rather questionable variety-house.” Mechanics' Hall included a lecture room in 1857 to assist young men learning “the useful arts.”

Drama was important to the doomed, crowded Confederate capital city. The burned Marshall Theater was rebuilt as the Richmond or New Richmond Theater at the height of the Civil War, opening in 1863. It closed in 1896 [Christian 452], a tired and down-at-heel veteran of many scenes. It seems likely that the Richmond Theatre reused at least a portion of the walls of the Marshall, since few structures were built in the city in 1863. The Greek Revival elements of the building are, however, unlikely to have been features of the previous theatre, built in 1819. Other theatrical venues prospered as well during the years that Richmond served as the Confederate capital. According to one source, these more popular venues included the Metropolitan Hall, the Richmond Varieties, a bawdy precursor to vaudeville, and the Richmond Lyceum [Kathyrn Fuller-Seeley. Celebrate Richmond Theater (Richmond: The Dietz Press, 2002).

|

|

Richmond Theatre seen on the

1876 Beers Map of Richmond.

|

The Richmond Theatre, which was about 160 feet deep (the size of a Richmond lot), stood four stories tall. The regular windows on the front and west side do not give any clue of the varied rooms within (some windows on the west side may be false windows, but light was needed on the interior for work associated with preparing for the plays). Like most fully equipped theaters of the time, the Richmond Theater did not have a fly loft for raising sets above the stage.

|

|

Richmond Theater shortly before

demolition in the 1890s.

|

As an important civic building, the Marshall Theater was given the full form of a temple. The building was detailed in the Greek “Tower of the Winds” Corinthian order with fluted three-quarter engaged columns on the inset front flanked by pilasters called “antae,” which continue along the west side separating every second window bay. The ornate Corinthian order was appropriate for a building used in the pleasurable festivities associated with drama. Entrance was through five openings in the first floor front, which was detailed to provide a basement to the temple front above.

|

The interior of the Richmond Theatre soon after the Civil War. The illustrator appears to have increased the dramatic value of the political meeting depicted by combining a view of the proscenium and boxes from the seats with a view of the auditorium from the stage. http://richmondtheatres.tripod.com |

The images of the interior shows that it was similar to other antebellum American theaters and that it continued the tradition of a central pit surrounded by raised horseshoe seating. Like other theaters derived from English models such as the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, the angled boxes to either side to the stage were flanked by colossal fluted Corinthian columns.

The history of theater in Richmond did not end with the burning of a significant portion of the city, in fact the Richmond Theatre wasn't harmed at all and the plays continued. The late nineteenth century saw the further diversification of entertainment. Increased disposable income among the urban working class encouraged the breakdown of theatrical productions into high- and low-brow and the introduction of competition among a growing number of theaters, although entertainment in Richmond at all levels continued to have a decidedly "Southern" plot and cast of characters.

This account is continued in Part Two, located here.