Showing posts with label Fragments. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Fragments. Show all posts

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

Rural Extensions: Dinwiddie County Architecture

All through the winter, Urbanismo has been at work far from our customary haunts. We have been occupied several days a week with the cataloging of old houses in one of the quietest and least urban of places: Southside Virginia. There we have visited some of the most powerfully evocative places from a seemingly ancient past in the venerable county of Dinwiddie. The landscape is made up almost entirely of small winding roads, modern agricultural businesses, crossroads churches, pulp-wood plantations in every stage of propagation from clear-cut to mature, and abandoned country stores (the stretch of Route 1 south of DeWitt is startlingly beautiful, quiet, and undeveloped). The county has been spared much of the devastation of suburban sprawl due to a large extent to the lack of economic growth in the adjoining city of Petersburg, yet it has suffered a terrible forgetting nonetheless.

The small houses of freed slaves and tenants, the farmhouses of the proud black and white landowners of the post war and early twentieth century can be seen in overgrown fields, most abandoned and unrecorded. Great plantations and middling mansions, set up to be showplaces of order in a now invisible landscape, are to be seen only in truncated remnants, sometimes perched uncomfortably in center of now-dated housing developments, many shorn of their accompanying villages of outbuildings and barns. When these outbuildings survive to be recorded by us, they are usually dilapidated and disused. Often the old houses serve as weekend or commuter homes. Our experience shows that almost no-one is at home during the week in Dinwiddie County.

While much farming takes place in the county on a variety of scales from small to large, a drive down one of the many newly forested roads is a constant reminder of the wreckage of a farm-based life across the state. Here there is none of the lush but shallow horse-oriented landscape that has replaced authentic small farms in areas colonized from the cities. Hunting camps and clubs abound. The most rewarding winter sights are the silhouetted groves of oaks that cluster around many farm houses and churches, set aside for the comfort of the muggy Southside summers.

The traditional farm life lives on among a number of older farmers, some of whom spoke to us of farming with horses and mules in the 1960s and later and whose farms are still replete with granaries, corn cribs, hay barns, and the tall log dark-fired tobacco barns so characteristic of the county’s fields. The old patterns of stability continues at a greater depth under the surface, harder to detect for those who don’t take part, but the empty trailers and proliferating roadside Cape Cods indicate the rise and triumph of another way of using the land. One is reminded of the closing, elegiac words of Henry Glassie’s now-classic study of conservative architectural and farming traditions in the Piedmont counties of Goochland and Louisa:

The old farmer of Middle Virginia is left standing alone at the end of a row. He watches, without motion, the dust spun from the auto’s tires settle through his garden. He lifts his chin from the back of his hand, his hand from the hoe. He shoulders the hoe and crosses the yard, glancing to the left at the sleek mule in his pen, and drops himself into a chair on the porch, where, efficient and swift, the hands of his wife click snap beans into a pot. Staring down into the middle distance, he says to himself alone, “Many changes, many changes, many changes, many changes.”

Henry Glassie, Folk Housing in Middle Virginia, 1976.

The first forgetting of Dinwiddie was the destruction in the Civil War of all its public records before the 1830s. A survey sponsored in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration first inventoried the county’s oldest houses, already in attenuated condition. The loss of memory was scarcely made up by a thin record of owners and dates attached to blurred and enigmatic photographs. Antiquarianism had overtaken the recorders; in keeping with the times, 1830 was considered the terminus ante quem of significance in furniture and architecture. Everything later was discounted. The eighteenth century was most honorable. Invented dates have since been assumed for many houses far in advance of possibility. It is astoundingly difficult to say for sure when and for whom many of the oldest and most important houses were built (and there remain quite a few).

The second forgetting has been the destruction of the historic landscape. Since the mid-twentieth century the loss has been disheartening. Two-thirds of the houses recorded in a survey of pre-1830 houses done in 1969 are vanished. Where ten years ago, most old houses looked out at the world through the refractions of mortised wood sashes, today almost every occupied dwelling in Dinwiddie stares at the viewer with the irrevocable, sterile glare of lightweight vinyl windows. Similarly, vinyl siding renders mute and hulking the delicate solidity of a well-built country church. To the eye of an historian of the rural landscape, the visible wreckage is so great in a few areas of the county that it is almost as if a war has devastated the countryside and left only ruins. The invisible transformation of the people of Dinwiddie may only be less palpable to outsiders.

The industrialization of the activity of building and of maintaining existing building completes the process. It becomes increasingly impossible to make traditional decisions, due to the cost and unavailability of materials and workmanship and of the memory of their meaning. In the end, however, it turns out that it is not the houses that matter but what goes on in them. As traditional patterns are lost, the rural order deteriorates from community into mere arrangement. It is all too likely that cataloging of artifacts serves no civic purpose here, except perhaps to set apart some products of the former times, undeniably hallowed by their close connection with the powerful current of human life lived in liberty, what Aristotle called “the Good Life.”

Labels:

Continuity,

Crisis,

Dinwiddie,

Forgetting,

Fragments,

Middling,

Order

Wednesday, December 2, 2009

The Passaggiata in Hell

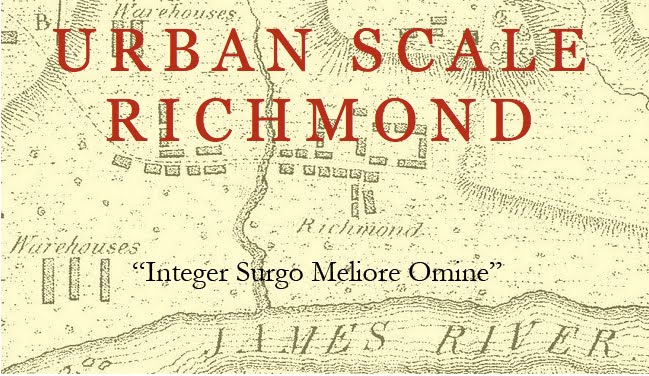

Richmond has lost the key to its stockpile of urban meaning. Meanwhile, the commercial life of the city has been transported to the outer suburbs. Short Pump Town Center (and Stony Point Fashion Park) are Richmond's newest shopping centers.

Short Pump is an urban desert. It is a parody of a city. Its architecture is sterile, banal, and without imagination, exhibiting no architectural unity or integrity. This was not entirely true of earlier shopping centers. Mid-twentieth-century shopping centers and malls such as Willow Lawn and Southside Plaza were unified by an architectural idea- in this case, that of modernism- much as the great metropolitan markets of the past exhibited architectural unity. As a commercial mart, Willow Lawn made no attempt to memorialize the past. And at any rate the shopping centers of the 1950s were aligned with major shopping streets.

“Downtown Short Pump” represents an unprecedented intrusion into the ancient patterns of humane life. It well merits its nickname at Urbanismo: “the Outer Circle of Hell.” Like chaos, Short Pump is without form and void, because it is changeless, timeless, one-dimensional, and circular, an endless passaggiata.

Short Pump has a few of the traditional features of a marketplace. Its monuments, such as a trite statue of Patsy Cline and the central fountain made up of a variety of hand pumps are humorless, literal, and derivative tropes on the monumental program of the actual city. It is a controlled environment with a fully developed literature of commerce. In its attempt to supplant the city, Short Pump Town Center has constructed a diminuative founding myth.

Markets are properly miniature cities. The order of the marketplace is immediately apparent. Orthogonal aisles like streets organize the stalls. The market is placed in the urban context and responds to its patterns. While markets and fairs are controlled sectors of the city, they contain individual proprietors who are responsible for their success or failure. Although the quality of their produce is carefully policed by the city, markets offer no guarantee of happiness. Unlike the vapid crowds at Short Pump, markets are frequented by people from all stations of life. A flaneur is unlikely to find pleasure at Stony Point Fashion Park.

While its open air plan is welcoming to pedestrians, Short Pump Town Center is the antithesis of a real market and far less subtle even than an American shopping mall. Its essentially circular form defies any ordering principle both locally and on an urban scale. It doesn’t matter where you are in it. A sleepy urbanist might mistakenly see it as an improvement over a shopping mall because it more self-consciously resembles a town. In fact, it is not a fragment of a city but a commercial whirlpool.

Short Pump is an urban desert. It is a parody of a city. Its architecture is sterile, banal, and without imagination, exhibiting no architectural unity or integrity. This was not entirely true of earlier shopping centers. Mid-twentieth-century shopping centers and malls such as Willow Lawn and Southside Plaza were unified by an architectural idea- in this case, that of modernism- much as the great metropolitan markets of the past exhibited architectural unity. As a commercial mart, Willow Lawn made no attempt to memorialize the past. And at any rate the shopping centers of the 1950s were aligned with major shopping streets.

Willow Lawn soon after construction

“Downtown Short Pump” represents an unprecedented intrusion into the ancient patterns of humane life. It well merits its nickname at Urbanismo: “the Outer Circle of Hell.” Like chaos, Short Pump is without form and void, because it is changeless, timeless, one-dimensional, and circular, an endless passaggiata.

An axial view of one of the tentacles of Short Pump Town Center

Short Pump is changeless (the owners pride themselves on its seamless maintenance program). It is timeless (the recorded music is always playing). It is one-dimensional and undifferentiated, while the city is endlessly varied but unified (it is differentiated within an underlying matrix of order). It is circular-even though there are different paths, ultimately the experience consists in walking in circles, like the mall-walkers who avoid climate and traffic to get relentless exercise. Such anti-urbanism was not a characteristic of earlier manifestations of the shopping center. The ancestor of the mall, the nineteenth-century galleria, functioned as a street and was an integral part of the city, aligned with the larger civic life.

Galleria Mazzini, Genova

Short Pump has a few of the traditional features of a marketplace. Its monuments, such as a trite statue of Patsy Cline and the central fountain made up of a variety of hand pumps are humorless, literal, and derivative tropes on the monumental program of the actual city. It is a controlled environment with a fully developed literature of commerce. In its attempt to supplant the city, Short Pump Town Center has constructed a diminuative founding myth.

The "Short Pump Fountain" at Short Pump Town Center

Markets are properly miniature cities. The order of the marketplace is immediately apparent. Orthogonal aisles like streets organize the stalls. The market is placed in the urban context and responds to its patterns. While markets and fairs are controlled sectors of the city, they contain individual proprietors who are responsible for their success or failure. Although the quality of their produce is carefully policed by the city, markets offer no guarantee of happiness. Unlike the vapid crowds at Short Pump, markets are frequented by people from all stations of life. A flaneur is unlikely to find pleasure at Stony Point Fashion Park.

While its open air plan is welcoming to pedestrians, Short Pump Town Center is the antithesis of a real market and far less subtle even than an American shopping mall. Its essentially circular form defies any ordering principle both locally and on an urban scale. It doesn’t matter where you are in it. A sleepy urbanist might mistakenly see it as an improvement over a shopping mall because it more self-consciously resembles a town. In fact, it is not a fragment of a city but a commercial whirlpool.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Vestiges of the Venerable City

Several years ago the architecture club at the Governor's School organized an escorted midnight bicycle trek to visit Richmond's architectural monuments called the "Architectura." On this cold and rainy night, Urbanismo presents, sans police motorcycles, a collection of urban survivals; a palimpsest of the city's decayed furnishings that serve as evidence of the changing ways our city orders its life. This series will continue as we uncover more telling fragments in our midst. The title of our tour comes from the name of Clay Lancaster's memorable book on Lexington, Kentucky.

European and American cities tended to identify streets, starting in the nineteenth century, with brilliant blue enamel panels attached directly to street corner buildings. As the years have passed most of these pedestrian-scaled way markers have eroded away. After an hour of searching Urbanismo found this weather worn pair of signs on a Jackson Ward corner we pass nearly every day.

As Richmond's suburbs expanded, this sort of street sign was used at most intersections, attached to the top of an ornamental cast iron pole. In the 1960's, most of these were discarded and replaced by sheet metal signs bolted to the top of older poles or new pipe columns. In some areas, the small upper panel held the number of the square or block, while on Monument Avenue the names of the cross streets were placed there. Here, the traditional ultramarine blue enamel panel survives in a rare example at the Lee Monument. The cast iron holder is attached to the standard by a decorative leafy band. Only two or three of these signs were missed by the city engineer.

A late night correspondence is attempted at the surviving cast iron mail box on the corner of Monument and Cleveland near the Maury monument. Its human scale, heavy counter-balanced lip, and endearing resemblance to an antique toy imbues even the Federal Government with urban panache. One imagines its rather improbable survival as the result of a very determined Richmond matron going to great lengths to convince the postmaster that this box was essential to the neighborhood's well being. Its fresh paint and up-to-date stickers proclaim that this amenity "has gotten over" the bureaucratic hump and will probably be with us for another hundred years. Two mail pickups a day in 1960 enabled our aunts to keep in close communication with their friends and relations.

Drinking fountains were a favorite civic gesture of temperance societies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This one provided water to visitors in Byrd Park and was supplied with a mounting block for children. It takes the form of an elegant Roman wall fountain. The upright tablet is supported by carved granite volutes. The basin is edged by an ornamental molding resembling a wreath of bound reeds suggesting the resolution and unity of the uncompromising band of donors. The inscription reads: "This fountain is erected by the Women's Christian Temperence Union of Richmond and Henrico County and their friends in Memory of the Crusaders of Hillsborough who went out December 19th 1873 with the weapons of prayer and faith in God to overthrow the liquor traffic."

"In memory of one who loved animals."

This carved marble fountain ornamented with four masks spouting fresh water was placed in the center of Shockoe Slip for the use of horses and oxen in this commercial district not far from the north end of Mayo's Bridge. One of Richmond's most sophisticated amenities, it clearly reminds us of the relation of Richmond to the great cities of the West.

Richmond was supplied with several publicly maintained artesian springs. City residents preferred their water for drinking and cooking. This neglected spring near Shield's Lake in Byrd Park, set in a circular cobblestone enclosure, was in regular use into the 1980's. It provided a cool grotto in the hot summer.

Similarly, this concrete exedral fountain supplied the residents of the northern suburbs. It is located immediately on the side of the Richmond-Henrico Turnpike where this nineteenth-century super highway runs through a deep ravine created by Cannon's Run-- the site, in the eighteenth century, of the Widow Cannon's pasture.

The "Richmond Settee" survives here at the end of Grace Street overlooking Shockoe Bottom. These cast iron benches were produced in Richmond for Capitol Square and other city parks in the late nineteenth century. They are modeled on a similar settee created for New York's Central Park. One or two examples remain in Capitol Square. In the days before air conditioning, the park bench functioned as an outdoor living room for families and individuals seeking fresh air and the company of their fellow citizens. [Update: Nov 19, 2012- the settee is no longer here]

Labels:

Fountains,

Fragments,

Furnishings,

ismo,

Order,

Street Signs

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)