|

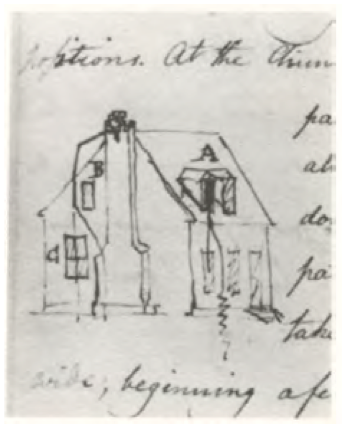

| Watson Ho., Detail of Madison Map of 1818 |

The tract of undeveloped land to the north and east of the

County Road was known as Watson’s Tenement. It had been leased by

Philip Watson, merchant, from William Byrd III- the lease appears to have been

renewed in 1757. It then comprised 128 acres and included, according to the

lease of 1757, a brick dwelling “where the said Philip now

dwelleth,” a brick store, and a frame

granary. It seems likely that the brick house was the same as the one 1/2-story

dwelling that later served as the Council House and the town residence of Col.

John Mayo. The appearance of that house

is known from a sketch done in the notebook of B. Henry Latrobe in 1798,

showing the damage done to it by a lightning strike.

|

| The house apparently built for Philip Watson, later the Council Chamber from B. Henry Latrobe, Mayo House, Notebook, 1798 |

The irregularity of Watson’s Tenement as it sloped down from the eastern margin of the Shockoe Hill plateau meant that it was slow to be incorporated into the city’s official grid. Probably as a result, parcels of land at the top of the hill were available for use by public institutions like schools (the Academy of Monsieur Quesney and the Medical College), a theater (the Richmond Theatre and the later Monumental Church), and churches (the Baptist Meeting House). At some point, the city acquired a larger tract of between two and three acres spanning Franklin Street along the west side of the creek for civic purposes, including the eventual construction of the City Jail. Missing city records mean that it is difficult to say in what decade the city acquired the section from the Turpin heirs. Minutes of the Common Hall are missing from May of 1795 until January of 1808 and no mention of the acquisition is recorded in the deed books. The notorious sites associated with the practice of slavery, such as Lumpkin’s Jail and the slave auction houses were located on the part of Watson’s Tenement along the creek to the south of Broad Street.

|

| Jefferson layout for the three Capitol squares, 1780, from Reps. Names of the original lots owners are shown. |

Shockoe Hill was transformed by the arrival of state government. The 1779 act that relocated the capital to Richmond from Williamsburg authorized the Directors of Public Building to find a location for the government buildings in the “open and airy part” of the city. Two locations were proposed by the major landowners in two bluff-top locations: Shockoe Hill and Richmond [Church] Hill. In the following year the General Assembly authorized the appropriation of a site on Shockoe Hill for a new four-part government complex including a “Capitol” for the legislature, a “Halls of Justice” for the courts, a “State House” for the executive boards and committees, and a residence for the governor. Richard Adams, owner of much of the land on Richmond Hill, thought that he had Jefferson’s promise and broke off his friendship when his proposal of twelve lots for the public buildings on Richmond Hill was rejected.

The process of valuing the land to be requisitioned for public use on Shockoe Hill began in 1783. The present site of Capitol Square seems to have been considered from the first, but two tracts that were also considered for taking comprised an area of thirty acres that was part of the former Watson Tenement. This parcel belonged to Horatio Turpin and his brother Dr. Philip Turpin, sons of Thomas Turpin, Thomas Jefferson’s uncle. It was located on Council Chamber Hill, to the east of the County Road [Governor Street]. Owing to the loss of records, including those pertaining to the General Court in Williamsburg, where the Byrds recorded most of their transactions, the history of the property is vague. As we have seen, the Turpins acquired Watson’s Tenement in its entirety after the lease was vacated, well before 1779. It was in that year that Thomas Jefferson, during his term as governor, occupied a house near the corner of Thirteenth and Broad belonging to Thomas Turpin.

Horatio Turpin, deemed the “owner of the lots most valuable for public use,” offered the thirty acres on the Council Chamber Hill for sale to the state and, for free, two 1/2 acres of land that were part of the tract. It included the compact brick building identified as “the house now used by the executive,” known as the “council chamber.” This was offered to the state as the site for the governor’s house [Journal of the House of Delegates 27 June 1783]. This parcel, later the home of John Mayo, would have made an excellent and scenic location for the executive mansion. It was later proposed as the site of a villa for the Mayos by B. Henry Latrobe.

Other lots were valued as well from 1781 to 1784. These

included all the lots that would make up Capitol Square. Most of these were

empty of buildings, but at least two lots on the immediate site of the Capitol

contained buildings. John Gunn had built two houses, occupied by himself and a

tenant, on lots 391 and 404. In addition two lots near the future site of the

Governor’s Mansion, owned independently by cooper John Ligon and

merchant Zachariah Rowland, included valuable buildings. The large frame house

on lot 357, owned by Rowland, was used for the next twenty years, with

increasing levels of dissatisfaction, to house the governor and his

family. This dwelling was close to the

County Road, which it faced, and was sited well below the level of Capitol

Square. Since, according to the 1782 tax

lists, Rowland had arrived in Richmond no earlier than 1780, and was not

registered with this lot in 1782, it seem likely that someone else had it built

at an earlier date (lot numbers are missing for this ward in the tax

list).

The general location was finalized in 1784, when the unitary Capitol building, designed to house all the functions of government, was commenced at the center of the square. The Directors of the Public Buildings decided not to use the thirty-acre site purchased from Turpin, and the legislature returned the land, for which he had not been paid. The state kept the two-acre Council Chamber part of the site and traded it for another portion of the tract just across the County Road from the governor’s house. This lot was already in use as a garden, presumably for vegetables to supply the governor’s table and to provide an attractive setting across from his front door.

In 1787, Turpin was informed that “the public had no occasion for the use of any part” of his land, “except two acres. . . for the purpose of having buildings erected thereon for the residence of the Governor which buildings had they been erected, would have greatly enhanced the value of your petitioner’s property lying adjacent.” Turpin petitioned in 1791 for redress for the loss of value to his property [Richmond City Legislative Petition, 11 Nov. 1791, Library of Virginia]. He continued to sue for relief until well into the nineteenth century, finally receiving compensation for the loss of the two acres in 1809. Meanwhile he had sold the remainder of the Council Chamber tract to Col. John Mayo in 1789.

The Turpin tract was entirely in the hands of Philip Turpin by 1775. He had laid out the flat part at the top of the hill in lots conforming to the adjacent grid pattern by that date, when he sold lots no. 781 and 782 to James Monroe [Richmond City DB 1:43]. The land on Council Chamber Hill and sloping down to the Shockoe Creek he sold in larger unnumbered tracts. As we have seen, these less likely tracts became acceptable sites for public and civic uses. In 1786 he sold a lot to the trustees of the Quesney Academy [Richmond City DB 1:119], which would, after the Richmond Theatre burned, become the site of Monumental Church. At that time he guaranteed that Broad Street (“the Main Street on Shockoe Hill”) should be extended along the entire frontage of the Academy lot. The Baptists acquired a lot east of the Academy.

|

| Map showing location of the Latrobe Theater |

The eastern edge of Shockoe Hill became a prominent location for civic and academic buildings. In the late 1790s it was proposed as the site for a great new Episcopal Church which would have effectively replaced Henrico Parish Church (St. John's) on Church Hill. This church was proposed for an extremely prominent location on axis with (in the center of) Broad Street, appropriate for the position of an established church, a position still held in some contention for the descendent of the Church of England. The church, seen roughly sketched in on a plan of the area drawn by architect B. H. Latrobe, was never built, nor was Latrobe's famous hotel/theater combination seen just above. The history of the eastern slope of Shockoe Hill is continued in part here.