"Consuls, emperors, and popes, the great men of every age, have found no better way of immortalizing their memories than by the shifting, indestructible, ever new, yet unchanging, upgush and downfall of water. They have written their names in that unstable element, and proved it a more durable record than brass or marble."

Hawthorne, The Marble Faun, 1860

[Fountains] are sited throughout [Pompeii], all very similar to one another and none very elaborate. While clearly more utilitarian than decorative in form, their siting is a different matter, for as we have seen, they so clearly contribute to the general urban structure that we must conclude that their placement took more into consideration than the utilitarian demands of the hydraulic engineers.

C.W. Westfall, Learning From Pompeii, 1998.

|

| Richard Worsham, Proposed fountain for 17th St Market |

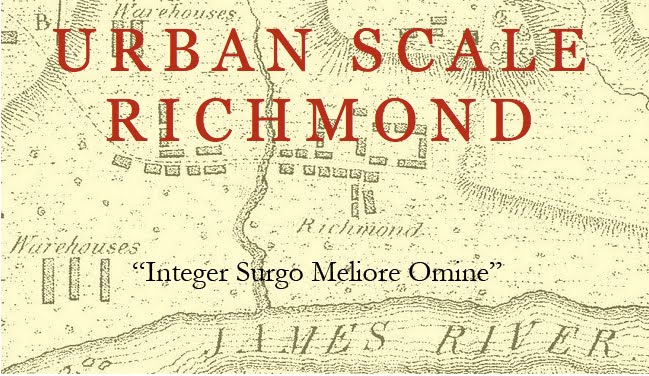

From a purely functional perspective, Richmonders, from the earliest date, relied on springs and public wells for water. As the nineteenth century passed, Richmond joined other traditional cities in the intentional use of water to mark out the public realm and to reinforce the city’s relationship with a tamed and ordered nature, while at the same time providing access to element required for life by both people and animals.

The city's access to water began at a very basic level. Public wells at street corners and a spring located south of Main Street sufficed for the town’s water supply in the eighteenth century. By 1808, however, the city, following national trends, used ingenuity to improve the purity and volume of the supply. Water was now conveyed in wooden pipes to the market at Seventeenth Street from a spring near Libby Hill. The resulting terminal fountain at the City Market must have been a familiar and significant destination for farmers, patrons, stall-holders, and their thirsty draft animals, not to mention the residents of all sorts that relied on that and similar public sources of water placed throughout the town.

|

| Richmond's City Hall, site of a public well in the early nineteenth century. |

The city was constantly expanding and improving its rudimentary water system. As technologies became accessible, the city applied them to the acquisition of addition supplies of water for drinking and fire prevention. In 1816, the common hall (city council) agreed to sink a well in Broad Street near the new Courthouse, which was located at the site of the current Old City Hall [Common Hall, 27 May 1816].

By 1830, Richmond’s water supply "consisted of public wells at the street corners and several public hydrants with water conveyed in wooden pipes from a spring near Chimborazo Hill and from one in the Capitol Square” [Christian, 1912, 115]. In 1827, the Common Hall had issued an order forbidding tampering with the city’s public water supply, including wells and pumps along H Street (Broad Street) installed at the city’s expense and the wooden pipes, placed by “sundry liberal and deserving inhabitants. . . [who] have at their own expense, placed wooden pipes through which water is conveyed from the Basin of the Canal, through the Main Street of the said City as far as Shockoe Creek, and have erected fountains or jets in different parts of the said pipes, whereby many Citizens are supplied with water, and in case of Fire in that part of the city, great advantages may be experienced from the water supplied at the said Fountains or Pumps. . . .” [Ordinance for keeping in repair the Fountains in the Main Street of the city of Richmond, 16 Nov. 1827].

In 1829, the City proposed an expanded "watering" of D and E streets (Cary and Main) from the Basin at 11th Street to Shockoe Creek, using iron pipes, at a cost of $5,631.64 [Common Hall, 28 May 1829]. A pump on Fourteenth Street was also proposed for use by fire companies. In the same year, Nicholas Mills ceded to the City a twenty-five foot-wide street through his lot from 7th to 8th street, giving access to a tract containing Gibson’s Spring, guaranteeing "open access to the said Spring . . . reserved for public purposes” [Common Hall, 8 June 1829].

A new system was opened in 1832, supplied by a water-powered pump with a capacity of 400,000 gallons of poorly filtered canal water per day. This system served to fill a 4,000,000 gallon reservoir. Water was distributed through twelve miles of pipe to both public and private locations. The first private hydrant was in the yard of Corbin Warwick on Grace Street between Fifth and Sixth Streets [Christian 1912, 115].

|

| Detail from 1865 view of Castle Thunder showing an iron hydrant on the NE corner of 18th and Cary Streets. The hydrant was detailed like a fluted Doric column. |

In ancient times, the provision of water in cities had been delivered at regularly placed urban nodes. From Pompeii to Paris, water outlets minimally required for the civic good have been harnessed to the larger urban project, underlining, by their sensory contributions, the significance of selected urban intersections and plazas. In Richmond, as elsewhere in the region, fountains or basins were provided at major entry points to the city for the watering of draft animals and herds. Hydrants were found at certain street corners for use in filling pitchers, tubs, and fighting fires.

The value and provision of water to city populations was one of the many topics that exercised the minds of early-nineteenth-century planners. In thinking about public water supplies, educated persons as a matter of course compared their plans to improve hygiene with the public fountains and baths of ancient Rome. They also tried to effect the most scientific and economical provision of water for the public.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, an English architect who began his American career in Richmond, was an advocate of public waterworks in Philadelphia, where outbreaks of disease had decimated the city. Such epidemics were sometimes associated with impurities in the water supply. Latrobe completed Philadelphia's public water system in 1801. In postscripts to his proposal for the waterworks, dealing with fountains and public baths, Latrobe displayed his characteristic interest in the effects of and correction of local climatic conditions and his studied opinion that the value of water justified the imitation by Americans of the indulgent practices of despotic European countries (by which he meant imperial Rome).

|

| Latrobe's Center Square Pump House, Philadelphia (1799-1801) |

According to one study, Latrobe asserted that "the fountains, which would supply the poor of the city with free water, would also provide the 'only means of cooling the air.' Air cooled by the agitation of water was, Latrobe asserted, “of the purest kind.' While it is most likely that Latrobe was referring to physical purity (here significant because miasmatic theory charged impure air as a source of disease), the word recalls a classical climactic tradition, which emphasized air as the medium which communicated the specificities of the environment to the human body" [Jennifer Y. Chuong "Art is a Hardy Plant": Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the Cultivation of a Transitional Aesthetics, Thesis, Cornell University) 2007].

|

| Godefroys' landscape st the Capitol Square included cascades that occuied the gullies to each side of the Capitol [Mijacah Bates, Map of Richmond, 1832]. |

|

| 1850 Capitol Square Fountain seen in 1960 [RTD, Valentine]. |

The city developed as part of its amenities a series of artesian springs in parks and green belts on the city’s periphery for public use. These also had a significant ornamental role, using water as a powerful symbol of the public good, organized and given form by the city. The water works at Byrd Park were developed in the 1880s, and the significance of the huge reservoir was later dramatized by a miniature cascade placed at the southern end of the great urban cross-axis of the Boulevard.

|

| Cascade at the Southern end of the Boulevard axis. The fountain represents the public water supply housed in the large reservoir just behind. |

|

| Monroe Park Fountain, Post Card, c 1905 [VCU Special Collections] |

Drinking fountains were a favorite civic gesture of temperance societies in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Richmond's temperance fountain, located near the reservoir, provided drinking water to visitors in Byrd Park and was supplied with a mounting block for children. It takes the form of an elegant Roman wall fountain. The upright tablet is supported by carved granite volutes. The basin is edged by an ornamental molding resembling a wreath of bound reeds suggesting the resolution and unity of the uncompromising band of donors. The inscription reads: "This fountain is erected by the Women's Christian Temperence Union of Richmond and Henrico County and their friends in Memory of the Crusaders of Hillsborough who went out December 19th 1873 with the weapons of prayer and faith in God to overthrow the liquor traffic."

|

| Capt. Charles S. Morgan gave this marble fountain to serve draft horses at the center of the city's tobacco warehouse district. It is inscribed "In Memory of One Who Loved Animals." |

The Monroe Park fountain was followed by similar structures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including a one depicting a heron in front of the Governor’s Mansion (unfortunately replaced with a very conventional iron one during the Robb administration).

|

| Wayside Spring, Forest Hills Park [https://foursquare.com/v/wayside-spring/4c73a7667121a1cda29a65d1] |

|

| Kanawha Plaza Fountain, located as part of a plaza designed by Robert Zion of Zion & Breen, completed in 1980 |

More recent fountains, such as those at the Kanawha Plaza at the James Center, installed during urban improvement projects in the mid-twentieth century, replace the conventional allegory of nature projected by earlier fountains with a literalism that fails to convince the viewer of either its natural origins or its cleanliness.

|

| Libby Hill Fountain, 1990s. |

.png)