Proposed market and square between Main and Broad Streets with Main Street Station on the left

This proposal for the Market at 17th Street is taken from a master's thesis presented in the spring of last year at the University of Notre Dame's School of Architecture with the title, "Politics and Commerce: The Architectural Rhetoric of the Market Hall." The renderings are watercolor washes hand drafted on 90lb Arches.

To see a more recent proposal for the Market at Seventeenth Street in the context of the Shockoe Ballpark Controversy, please visit

this recent post.

Please click on the images to zoom in (to zoom in even more right click and select "view image").

Aerial photograph showing the existing conditions of Shockoe Bottom and the 17th Street Market

THESIS

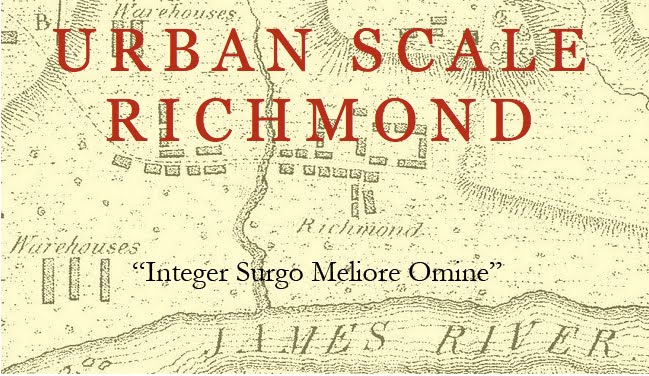

Following the theories of urban form developed by Carroll William Westfall and Saverio Muratori and his students, including Gianfranco Cannigia and Mario Gallerati, I propose to provide a new market set alongside an architecturally unified square in order to reassert the significance in Richmond of architecture at the urban scale in furthering the civic life and to function as a rhetorical tool to civilize the commercial activities of the market within the higher and more important political framework of the city.

View of the proposed Main Street facade looking up 17th Street

INTRODUCTION

Artists and architects, in the tradition of Socrates, have always questioned accepted truths and sought to translate them into the language of their own time. The process of allowing our judgment to be informed through the comparison of the way things are with the way things should be is the basis of successful design. Many of the accepted truths that dominated the urban and architectural discourse over the last seventy years have lost their force. It is increasingly clear that a different approach to our world and the way we live is unavoidable. But how do we determine what we should do? The pattern for thriving, beautiful cities is to be found in the long history of trial and error, of genius and imitation stretching beyond written record, but preserved in our building traditions. To operate traditionally is not concerned with preserving a specific programme or way of thinking, but with ensuring that our future is the best it can possibly be.

Insofar as nature is composed of stable, unchanging classes of things, including those of human activity, architecture is capable of clarifying the structure of the city. Through the judicious use of the orders, the depiction of famous narratives of the city, and its overall suitability, architecture provides a comprehensible framework conducive to the pursuit of the good life. Architecture thus functions rhetorically by embodying and explaining the order of the city through the imitation of nature.

In the Western city, with economic freedom connected with urban life, the market and the polity are architecturally linked and the market hall is the heart or center of the city. In republican polities it is has often been in the market building that architecture most prominently holds up the ideal of the good life lived in community. In order to make that order more visible, the civility which the market reinforces can be extended through the city’s neighborhoods by means of a series subsidiary markets deriving their form from the central building. By this means, the architecture of commerce can effectively embody the struggle between what is and what ought to be.

Nolli plan of 17th Street Market and surrounding area (proposed buildings are shown in brown)

PROJECT OVERVIEW

ARCHITECTURAL SCALES

The students of Saverio Muratori work within the understanding that cities and buildings are composed of a number of scales and that to be successful each part must engage its appropriate station in the hierarchy of the city or state. The Muratori approach is interested not only in individual buildings, but in the concept of the formal square, and on a larger scale, the forms of cities. This approach is based on the idea of a system of architectural scales which can be described or “read” using “synoptic tables” that compare traditional building similarities and differences from the scale of entire regions down to the scale of window treatment.

Section showing the proposed market in its context on Main Street, a model subsidiary or neighborhood market, and a proposed public fountain

The different architectural scales of the city embody the order of communal life which has the common good as its end. These various scales are hierarchically important according to the degree to which they deal with the public realm. More directly, parts of the city on the architectural, or building scale are subordinate to the urban scale, or “urban ensemble” in the words of Carroll William Westfall. Significant events in the urban scale might include civic places such as law courts, libraries, markets and baths. These places are more important than private buildings, but in turn subordinate to the larger, more public building which is the city. The various scales are represented by their use of similar components. Without similarity between these scales comparison between them would be impossible, and yet without difference their location in a higher order would be equally unintelligible.

Historically, the First Market in Richmond was the central public building in the life of the city, linking private interest and public good. Since its non-commercial functions and most of its market functions have been dispersed to other city institutions, the market’s dissolution can be seen as a major civic loss: of the face-to-face relationship of buyer and seller, the linkage of public and private life, and the elevation of civic discourse made possible by the rhetoric of good architecture.

TYPOLOGY

European (and by extension) American markets and market halls are formally linked to the stoa, forum, basilica, loggia, exchange, and bourse. Like their ancient models, they provide a covered place to transact business within an ordered framework. Thus, the arcades of the 1794 Market Hall at Richmond are related to a long tradition of civic architecture. Markets are almost always associated with extended arcades for both practical and symbolic reasons. Examples of arcades at hand include courthouses and the Williamsburg Capitol. The compass-headed window or door opening was generally reserved for public buildings. The Virginia examples had their models in England. The arcaded piazzas found at the Williamsburg Capitol and incorporated into courthouses in neighboring counties have their roots in English market halls and the courtyards of mercantile structures in London, Oxbridge colleges, and local buildings such as almshouses built in the seventeenth century. For more on the Richmond market please read our

earlier post.

View from market towards the old Loving's Produce building showing the proposed public square

PROPOSAL FOR A NEW MARKET AT SEVENTEENTH STREET

The 17th Street Farmers’ Market is operated and maintained in perpetuity as a public market where locally-grown and locally-made goods are sold directly by their producers. Independent local food producers, artisans, and crafts people are encouraged and promoted.

Current Market Mission Statement

Cities are places where people come together to pursue a common good which can only be achieved in communal life. Architecture serves this public good—politics is more important than architecture. The public realm is more important than the private realm. In order for the city’s prosperity to contribute to the common good, the market must be civilized. A market is not a city. A market serves private goods, but the city requires both public and private goods.

The current 17th Street Market sheds

The current market, consisting of a series of lightweight open sheds, serves as an anchor for community life by providing a setting for cultural and civic activities that complement the market and its location in downtown Richmond, but it does not succeed in the larger goal of reintroducing an armature of civic architecture into the marketplace. The intention of this thesis project is to reunite the old and new sections of Richmond, Virginia, to architectonically recover the commercial and civic life of the city by embodying its order.

The project will consist of a produce market and common hall for civic and cultural purposes and a resale market linked by a piazza that would serve the multiple purposes of deliveries, public entertainment, and strolling. The current night-time activities around the market will be accommodated within the market hall and piazza. The open areas will provide room for the crowds of revelers and an ordered context for the common life.

In order to effectively recapture the significance and civic value of the First Market to the city, the building will participate in the formal, poetic and material architectural traditions of the city. It will take into account the various scales of the city: the scale of building components, the architectural scale, and the urban scale. It is intended that this be the main public market for the city, but that there should be other subsidiary markets on the neighborhood scale. These smaller markets would be built as diluted versions of the First Market, reinforcing and explaining the order of the city, much as traditional libraries and post offices reveal through their scales the meaningful hierarchy of the city.

BUILDING PROGRAM

The principal First Market structure will consist of two parts: a South Market which will include a mixed public market on the first floor and a civic hall on the floor above and a North Market housing an open produce market on the first floor and city offices above. Permanent stall holders will be housed in an enclosed and secure accessible area in the South Market provided with garage-type doors opening to an exterior colonnade and connections for food storage and preparation. The narrower, northern portion of the market hall will open to the exterior through arcades and will house regular fruit and vegetable sellers like those now operating on a daily basis in the market.

Ground floor plan and elevation of the proposed market (the Main Street facade is toward the right).

The second floor of the North Market section will contain a large meeting room, smaller meeting rooms, a catering kitchen, toilets, and the offices of the Richmond City Board of Architectural Review. The existing mid-block alley will cross through a hyphen linking the two parts of the building at mid-point and containing the main stair, elevator, and public toilets.

Second floor plan and section through the proposed market

The First Market will provide a setting for the benefit of civic life. The renewed district will serve multiple purposes, including:

(1) a semi-weekly farmers’ market. Market stalls will be housed in an adjoining arcade. The adjoining square will provide access, parking for farmers’ vehicles, and additional movable market stalls.

(2) an area for festivals, performances, and public gatherings. Access will be re-opened along Franklin Street under the Main Street Station Shed to the important sites along the Richmond Slave Trail.

(3) a unifying center for a renewed market district, including a hotel fronting on the square, and new commercial/residential units based on the traditional basic building type of the city.

The elongated series of market buildings will respect the historic land divisions and take advantage of existing street paving and edging. They will occupy the same ground as the historic market. The new structures will recall the architectural forms of

preceding market halls on the same site and of versions of the building type over time. They will exhibit architectural diminution as the structures move away from the principal street.

Section through the historic market site cut along Shockoe Creek looking East

The square functions on the urban scale as a public room for the entire city. Like the Civic Hall above the market, it is treated with appropriate festive and ceremonial ornament. Historic Crane Street, currently barren, has become the focus of a new residential and cultural area off Broad Street. It will be possible to walk from the streetcar stop in front of the proposed cinema on the south side of Broad along a colonnade on the west side of Crane, to the covered walk around the new civic square.

Crane Street connects the square and market with Broad Street and the proposed theater, based on the Latrobe's unrealized design for a theater in the center of Broad on Council Chamber Hill.

The sculptural program celebrates the several myths of Richmond’s founding. The proposed houses along the west side of the square are modeled on the 1809 row of houses with a giant Doric order built by the Carrington brothers on Broad Street. Other basic row houses are proposed along Seventeenth Street and Crane Street.

The west side of the square refers to Carrington Row for an overtly ordered row house precedent

The South Market is supported on a brick arcade with applied Doric pilasters that refer to the colonnade of the former market. The upper story features an implied Ionic arcade with fully realized pilasters on the principal, Main Street, facade. The Main Street frontage contains a wide loggia for public use, joining other important brick public buildings along Main Street that feature arcaded elevations. The central tower that connects the south and north sections is modeled on the incomplete tower at the rear of Richmond’s Monumental Church. The open interior spans historic Arch Alley and connects the new commercial development between the market and the train station with the Market Hall.

The central tower connects the two market buildings and spans historic Arch Alley

The second floor of the South Market contains a multipurpose civic hall ornamented with Corinthian columns. A vaulted gallery fronts on Main Street. The second floor of the North Market contains offices for the city’s Board of Architectural Review and a hearing room fronting on Franklin Street above the loggia of the 24-hour coffee shop. Representation of this aspect of city government is particularly important in reinforcing the civilizing function of political life.

The market buildings are designed using load-bearing composite masonry walls, made of lime-based masonry blocks, faced with hand-made brick. It is roofed with slate and the eighteen-foot-tall ground floor is heated with in-floor radiant piping and is naturally ventilated using roll-up doors and large ceiling fans.

Axonometric rendering showing the load-bearing composite masonry walls

The square is treated with a large, diluted Doric pilaster order. The strip pilasters are flanked by a Tuscan suborder that alternately supports trabeated and arcuated openings. The unitary architectural treatment of the entire square is articulated to permit the uses of the interior rooms to speak on the exterior. It is derived from Roman Baroque examples and motifs, such as those found at the Sapienza and Piazza Santa Maria della Pace in Rome.

Sections through the proposed public square

The integration of the shops and residential accommodations across the west side is based on Richmond precedent. The farmers’ market north of Franklin Street is supported on brick columns with stone trim. A hotel located at the north end of the square extends into the second floor of the market. A large loggia in front of the hotel can be used as a restaurant. A triple entrance on the square’s south side rationalizes the irregular historic street layout in the area.

Detail of the public square between Franklin and Grace Streets

The market complex includes the following amenities:

(1) Secondary loggia on Franklin Street containing Coffee House

(2) Two-story Market Hall between Main Street and Franklin which includes a wide loggia on Main Street, permanent stands for goods, and a colonnade for vendors.

(3) Central tower with an archway at the alley crossing and ceremonial second-

floor access.

(4) A headhouse for the Farmer’s Market north of Franklin Street surmounted by a cupola for a bell and incorporating the police station and public toilets.

(5) Resale market in the former Loving’s Produce Building off the square.

(6) Formal square between Franklin and Grace for events and farmers’

market.

(7) One-story enclosed market between Franklin and Grace for resale market.

The new First Market complex described in this thesis serves to recapture the significance and civic value of commerce to the city. The building will participate in the formal and material traditions of the city. It participates in the various scales of the city: the building component scale, the architectural scale, and the urban scale, reinforcing and explaining the order of the city.

The Main Street facade