|

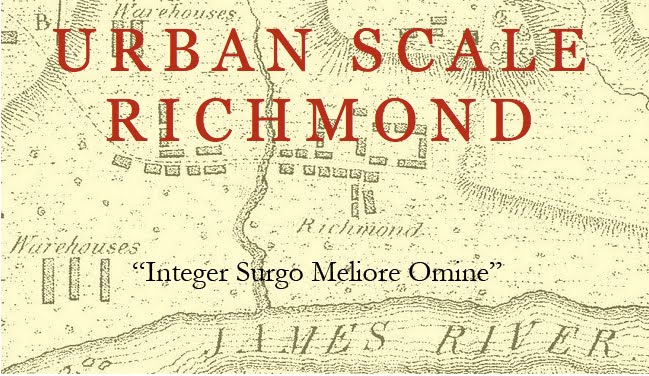

| Photographer Harry Stilson, Soldiers and Sailors

Monument beyond [Style Magazine: from Richmond in Sight]. |

The city’s monuments never stand alone: they join in loosely connected chains of meaning that extend across the city and through time to other cites around the world. We have explored the ways in which civic rituals like parades and processions make use of these armatures in this post.

As Lucien Steil has observed, many memorials record, not only celebrations, but times of disaster or suffering. Commemoration of great struggle and suffering "is not about remembering and reviving acute and relentless destruction, terror, fear, etc., but about overcoming these moments of unbearable pain by moral and material acts of reconstruction. . . . This creative sublimation of the experience of death and destruction, of horror and fear, into symbols of life, continuity and permanence is the paradoxical purpose of commemoration. . . . It is a necessary condition of any cultural endeavor of humanity" [Lucien F. Steil, "Reconstruction and Commemoration." American Arts Quarterly 4:3 (Winter 2015)].

The City’s Memorials

For the purposes of this discussion, these civic markers have been divided into three types: I. Memorials, II. Monuments, and III. Fountains. While each of these may combine some aspects of the others, mingling, for instance, sculpture and flowing water or bas relief and memorial inscription, most of the civic markers in the city can be chiefly identified under one or the other of these categories.

Justin Shubow of the National Civic Art Society has defined two of these civic elements:

In current parlance, “monument” denotes a large (approximately at least 1.5 times the height of an average man) useless permanent immovable structure that honors its subject and was designed to be seen as such. A monument is useless in the sense that it is not meant to have a function other than honoring and commemorating its subject. . . . All monuments are memorials, but not all memorials are monuments. Some memorials contain monuments. Monuments are clear and unequivocal in their meaning; memorials can be abstract and ambivalent. Monuments immortalize their subjects; the subjects of memorials can be permanently dead or finished. Monuments speak; memorials can stay silent. Monuments need no signage; memorials often do.An additional purpose for monuments is emphasized here: that of orienting the viewer within the city, both in the past and present.

The earliest memorials in Richmond were the grave markers in the cemetery surrounding St. John’s Church at the top of Richmond Hill near the northeastern entry to the city at the top of 23rd Street as well as in the city’s successive African American burial grounds (the first Burying Ground for Negroes and the other public and private African American burying grounds that replaced it after 1816) on the sloping sides of Shockoe and Academy hills. It appears that many of the earlier burials at the city's cemeteries were not marked with stones. Stone grave markers would have been the exception in favor of wooden head and footboards. Those early stone markers which do survive at St. John’s not only incorporate carved decoration, but include inscriptions praising the virtues of the dead.

|

| St John's Churchyard in the early 20th century |

Disestablishment of the church coincided with a need for an enlarged burial ground for whites. A first step was the purchase by the city, in 1799, of two adjacent lots on Broad Street to double the size of the burying ground to two acres. The city and church worked out a cooperative agreement for management of the graveyard that holds to this day.

|

| Shockoe Cemetery in 1865 showing overgrown lots and fenced graves with the City Almshouse beyond [Library of Congress] |

|

| Cenotaph tomb of William H. Cabell in Shockoe Cemetery |

|

| Turkey Island Obelisk, Henrico Historical Society |

The unusual obelisk built in 1772 below Richmond on the plantation known as Turkey Island is often cited as an early monument memorializing the “Great Fresh,” a catastrophic flood. It has, however, recently been proposed that the obelisk was not intended for this purpose, but was primarily a component in an important early English Baroque rural landscape design [William Rhodes, "Ryland Randolph and the Palladian Triangle of Colonial Central Virginia." Presentation at the VCU Architectural History Symposium, 2012].

Richmond’s first purposeful civic monument was a constituent but self-contained part of a larger, hybrid work of architecture. Monumental Episcopal Church was planned in 1812 and completed in 1814 to memorialize a deadly theater fire on the same site. Designer Robert Mills grafted a dramatic thirty-two-foot-square monumental Aquia stone porch onto the front of an equally unusual octagonal stuccoed brick church. Mill’s portico is the architectural setting for a monument in the form of a Neoclassical funereal urn symbolically representing the shocking loss felt by Richmond’s citizens. The portico can also be seen as a monument: a symbolically detachable loggia or templum with details and materials contrasting with the body of the church.

The relative independence of the loggia helps to justify the public funding of a sectarian church to memorialize members of the wider population. The exigencies of the situation suggested the hybrid nature of the monument; the city’s Episcopalians desired a new church and were prepared to build in the general area of the theater. The city improvised, not a new building type, but a largely unprecedented composite of models that would permit an effective memorial to those whose remains were indiscriminately mingled in the theater’s foundation. In combining the memorial to so large and diverse a group of victims in one monumental building, the city emphasized, not only a collective sense of loss, but a communal resolution to promote the public good.

Like the raised table tombs that appeared in St. John’s Churchyard in the early nineteenth century, the neoclassical cenotaph at Monumental Church formed a symbolic repository for the bones of the dead, which were actually mingled in the earth beneath the church. Their bones were set aside and marked so that examples would live on in the lives of the city as a whole, whenever a passerby saw the marker or read the text. The monument which consisted of a sarcophagus form topped by an urn, similar to those used in Mycenean times to contain the bones of the dead, is a linear descendent of the tumulus which covered the tomb central to the cults of the Ancient Greek heroes. A form of immortality was achieved when the place of burial was made of permanent materials and the memory of the great deeds of the tomb's occupant was kept alive.

The city’s expanding practice of monument-making also paid deference to the ancient importance of a founding myth, which we have explored here. In much the same way that Richmond was said, improbably, to have seven hills like Rome, in order to lend it a classical air, those responsible knew that by venerating its ancient founders the young city might acquire a sense of permanence. The first monument of the city’s founding may be the copper cross atop a rough pyramid of stones placed on Gamble’s Hill to mark the first visit to the falls by the English settlers. It was dedicated by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities in 1907 (and relocated to the Canal Walk in 1983). The monument reenacted the planting of a cross by Captain Christopher Newport three hundred years before, which served to claim the land for the English monarch. The new version was intended to gave legitimacy to the ongoing project of making a city.

The Mayo family, descendants of the city’s original surveyor, had lived for generations at Powhatan’s Seat, on the hill east of Richmond that probably served as the local seat of the Powhatan’s personal tribe. The Mayos carefully preserved at their house a talisman in the form of a stone said to have formed part of Powhatan’s house, sited in the native village at the falls which had been purchased by Captain John Smith and named by him “Nonesuch.” This stone, formerly located along the river, was moved to the crest of Chimborazo Park overlooking the river when it was displaced by the city’s gasworks about 1911. Oddly, William Byrd, the putative father of Richmond, who was an accomplished founder and namer of cities, which he once called “castles in the air,” was never honored with a monument at all, although his name has been applied to a park, a hotel, a theater, and a community center.

One of the city’s earliest outdoor monuments was a small marble obelisk set up in 1834 to memorialize a skirmish between the otherwise victorious British Queen’s Rangers and the Virginia militia. According to the marker on Grove Avenue in the Fan District, probably placed by veterans of the engagement, Virginia forces under Col. J. Nicholas had “driven in” Arnold’s picket on 4 January, 1781. Benedict Arnold had taken Richmond in late 1780 and a regiment under Lt. Col John Simcoe were returning from burning the foundry at Westham west of Richmond. This may have been the “scuffle” for which the nearby hamlet of Scuffletown was named [Drew St.J. Carneal. Richmond’s Fan District. Historic Richmond Foundation, 1996, 14-15].

The two hundredth anniversary of the incorporation of Richmond as a city and of its elevation from a county seat to the state capital was memorialized in 1982. A plaque was appropriately placed at the Old Henrico Courthouse on East Main Street to mark the site where, in the absence of any other city meeting place, there took place the initial election of the twelve members of the city's common hall and of its first mayor, William Foushee.

|

| Memorial plaque at the Old Henrico County Courthouse recognizing the election there of the city's first governing body. |

Although there were non-sculptural memorials set up before the Civil War, the Confederacy became the subject of the city’s greatest outpouring of memorial-making. The elaborate iron fence surrounding the Hebrew Confederate Cemetery was made in 1866. The posts consist of furled Confederate flags and stacked muskets, with a soldier's cap perched on top. The posts are connected by sabers and swords hung with laurel wreaths. The earliest large-scale monument, built in 1869, rose in Hollywood Cemetery to honor the thousands of dead soldiers buried around it. The ninety-foot granite pyramid reinforced a ritualized theme of loss and death. A large marble obelisk at Oakwood Cemetery in the city’s east end followed soon after funds were raised by 1871.

|

| Confederate Monument, Oakwood Cemetery |

|

| Confederate Monument, Hollywood Cemetery |

The memorialization of history became institutionalized soon after. Plaques recording locations and events were attached to buildings by the Confederate Memorial Literary Society in the first decades of the twentieth century, including the site of Libby Prison in 1911. The series of “Freeman Markers” named for author and editor Douglas Southall Freeman, who promoted them and wrote the texts around 1925, mark the locations of fortifications and battlefields in and around the city for the use of tourists and returning veterans.

|

| Freeman Marker |

|

| Confederate Memorial Plaque at the Old Henrico Courthouse on East Main Street |